|

I put the shotgun in an Adidas bag

and padded it out with four pairs of tennis socks, not my style at all,

but that was what I was aiming for: If they think you’re crude, go

technical; if they think you’re technical, go crude. I’m a very

technical boy. So I decided to get as crude as possible. These days,

though, you have to be pretty technical before you can even aspire to

crudeness. I’d had to turn both these twelve-gauge shells from brass

stock, on a lathe, and then load them myself; I’d had to dig up an old

microfiche with instructions for hand-loading cartridges; I’d had to

build a lever-action press to seat the primers – all very tricky. But I

knew they’d work.

The meet was set for the Drome at 2300, but I

rode the tube three stops past the closest platform and walked back.

Immaculate procedure.

I checked myself out in the chrome siding of a

coffee kiosk, your basic sharp-faced Caucasoid with a ruff of stiff, dark

hair. The girls at Under the Knife were big on Sony Mao, and it was

getting harder to keep them from adding the chic suggestion of epicanthic

folds. It probably wouldn’t fool Ralfi Face, but it might get me next to

his table.

The Drome is a single narrow space with a bar

down one side and tables along the other, thick with pimps and handlers

and an arcane array of dealers. The Magnetic Dog Sisters were on the door

that night, and I didn’t relish trying to get out past them if things

didn’t work out. They were two meters tall and thin as greyhounds. One

was black and the other white, but aside from that they were as nearly

identical as cosmetic surgery could make them. They’d been lovers for

years and were bad news in a tussle. I was never quite sure which one had

originally been male.

Ralfi was sitting at his usual table. Owing me a

lot of money. I had hundreds of megabytes stashed in my head on an idiot/savant

basis, information I had no conscious access to. Ralfi had left it there.

He hadn’t, however, come back for it. Only Ralfi could retrieve the

data, with a code phrase of his own invention. I’m not cheap to begin

with, but my overtime on storage is astronomical. And Ralfi had been very

scarce.

Then I’d heard that Ralfi Face wanted to put

out a contract on me. So I’d arranged to meet him in the Drome, but

I’d arranged it as Edward Bax, clandestine importer, late of Rio and

Peking.

The Drome stank of biz, a metallic tang of nervous

tension. Muscle-boys scattered through the crowd were flexing stock parts

at one another and trying on thin, cold grins, some of them so lost under

superstructures of muscle graft that their outlines weren’t really

human.

Pardon me. Pardon me, friends. Just Eddie Bax

here, Fast Eddie the Importer, with his professionally nondescript gym

bag, and please ignore this slit, just wide enough to admit his right hand.

Ralfi wasn’t alone. Eighty kilos of blond

California beef perched alertly in the chair next to his, martial arts

written all over him.

Fast Eddie Bax was in the chair opposite them

before the beef’s hands were off the table. "You black belt?"

I asked eagerly. He nodded, blue eyes running an automatic scanning

pattern between my eyes and my hands. "Me, too," I said. "Got

mine here in the bag." And I shoved my hand through the slit and

thumbed the safety off. Click. "Double twelve-gauge with the triggers

wired together."

"That’s a gun," Ralfi said, putting a

plump, restraining hand on his boy’s taut blue nylon chest. "Johnny

has an antique firearm in his bag." So much for Edward Bax.

I guess he’d always been Ralfi Something or

Other, but he owed his acquired surname to a singular vanity. Built

something like an overripe pear, he’d worn the once-famous face of

Christian White for twenty years – Christian White of the Aryan Reggae

Band, Sony Mao to his generation, and final champion of race rock. I’m a

whiz at trivia.

Christian White: classic pop face with a

singer’s high-definition muscles, chiseled cheekbones. Angelic in one

light, handsomely depraved in another. But Ralfi’s eyes lived behind

that face, and they were small and cold and black.

"Please," he said, "let’s work

this out like businessmen." His voice was marked by a horrible

prehensile sincerity, and the corners of his beautiful Christian White

mouth were always wet. "Lewis here," nodding in the beefboy’s

direction, "is a meatball." Lewis took this impassively, looking

like something built from a kit. "You aren’t a meatball,

Johnny."

"Sure I am, Ralfi, a nice meatball

chock-full of implants where you can store your dirty laundry while you go

off shopping for people to kill me. From my end of this bag, Ralfi, it

looks like you’ve got some explaining to do."

"It’s this last batch of product,

Johnny." He sighed deeply. "In my role as broker –"

"Fence," I corrected.

"As broker, I’m usually very careful as to

sources."

"You buy only from those who steal the best.

Got it."

He sighed again. "I try," he said

wearily, "not to buy from fools. This time, I’m afraid, I’ve done

that." Third sigh was the cue for Lewis to trigger the neural

disruptor they’d taped under my side of the table.

I put everything I had into curling the index

finger of my right hand, but I no longer seemed to be connected to it. I

could feel the metal of the gun and the foam-pad tape I’d wrapped around

the stubby grip, but my hands were cool wax, distant and inert. I was

hoping Lewis was a true meatball, thick enough to go for the gym bag and

snag my rigid trigger finger, but he wasn’t.

"We’ve been very worried about you,

Johnny. Very worried. You see, that’s Yakuza property you have there. A

fool took it from them, Johnny. A dead fool."

Lewis giggled.

It all made sense then, an ugly kind of sense,

like bags of wet sand settling around my head. Killing wasn’t Ralfi’s

style. Lewis wasn’t even Ralfi’s style. But he’d got himself stuck

between the Sons of the Neon Chrysanthemum and something that belonged to

them – or, more likely, something of theirs that belonged to someone

else. Ralfi, of course, could use the code phrase to throw me into idiot/savant,

and I’d spill their hot program without remembering a single quarter

tone. For a fence like Ralfi, that would ordinarily have been enough. But

not for the Yakuza. The Yakuza would know about Squids, for one thing, and

they wouldn’t want to worry about one lifting those dim and permanent

traces of their program out of my head. I didn’t know very much about

Squids, but I’d heard stories, and I made it a point never to repeat

them to my clients. No, the Yakuza wouldn’t like that; it looked too

much like evidence. They hadn’t got where they were by leaving evidence

around. Or alive.

Lewis was grinning. I think he was visualizing a

point just behind my forehead and imagining how he could get there the

hard way.

"Hey," said a low voice, feminine, from

somewhere behind my right shoulder, "you cowboys sure aren’t having

too lively a time."

"Pack it, bitch," Lewis said, his

tanned face very still. Ralfi looked blank.

"Lighten up. You want to buy some good free

base?" She pulled up a chair and quickly sat before either of them

could stop her. She was barely inside my fixed field of vision, a thin

girl with mirrored glasses, her dark hair cut in a rough shag. She wore

black leather, open over a T-shirt slashed diagonally with stripes of red

and black. "Eight thou a gram weight."

Lewis snorted his exasperation and tried to slap

her out of the chair. Somehow he didn’t quite connect, and her hand came

up and seemed to brush his wrist as it passed. Bright blood sprayed the

table. He was clutching his wrist white-knuckle tight, blood trickling

from between his fingers.

But hadn’t her hand been empty?

He was going to need a tendon stapler. He stood

up carefully, without bothering to push his chair back. The chair toppled

backward, and he stepped out of my line of sight without a word.

"He better get a medic to look at that,"

she said. "That’s a nasty cut."

"You have no idea," said Ralfi,

suddenly sounding very tired, "the depths of shit you have just

gotten yourself into."

"No kidding? Mystery. I get real excited by

mysteries. Like why your friend here’s so quiet. Frozen, like. Or what

this thing here is for," and she held up the little control unit that

she’d somehow taken from Lewis. Ralfi looked ill.

"You, ah, want maybe a quarter-million to

give me that and take a walk?" A fat hand came up to stroke his pale,

lean face nervously.

"What I want," she said, snapping her

fingers so that the unit spun and glittered, "is work. A job. Your

boy hurt his wrist. But a quarter’ll do for a retainer."

Ralfi let his breath out explosively and began to

laugh, exposing teeth that hadn’t been kept up to the Christian White

standard. Then she turned the disruptor off.

"Two million," I said.

"My kind of man," she said, and laughed.

"What’s in the bag?"

"A shotgun."

"Crude." It might have been a

compliment.

Ralfi said nothing at all.

"Name’s Millions. Molly Millions. You want

to get out of here, boss? People are starting to stare." She stood up.

She was wearing leather jeans the color of dried blood.

And I saw for the first time that the mirrored

lenses were surgical inlays, the silver rising smoothly from her high

cheekbones, sealing her eyes in their sockets. I saw my new face twinned

there.

"I’m Johnny," I said. "We’re

taking Mr. Face with us."

He was outside, waiting. Looking like your standard

tourist tech, in plastic zoris and a silly Hawaiian shirt printed with

blowups of his firm’s most popular micro-processor; a mild little guy,

the kind most likely to wind up drunk on sake in a bar that puts out

miniature rice crackers with seaweed garnish. He looked like the kind who

sing the corporate anthem and cry, who shake hands endlessly with the

bartender. And the pimps and the dealers would leave him alone, pegging

him as innately conservative. Not up for much, and careful with his credit

when he was.

The way I figured it later, they must have

amputated part of his left thumb, somewhere behind the first joint,

replacing it with a prosthetic tip, and cored the stump, fitting it with a

spool and socket molded from one of the Ono-Sendai diamond analogs. Then

they’d carefully wound the spool with three meters of monomolecular

filament.

Molly got into some kind of exchange with the

Magnetic Dog Sisters, giving me a chance to usher Ralfi through the door

with the gym bag pressed lightly against the base of his spine. She seemed

to know them. I heard the black one laugh.

I glanced up, out of some passing reflex, maybe

because I’ve never got used to it, to the soaring arcs of light and the

shadows of the geodesics above them. Maybe that saved me.

Ralfi kept walking, but I don’t think he was

trying to escape. I think he’d already given up. Probably he already had

an idea of what we were up against.

I looked back down in time to see him explode.

Playback on full recall shows Ralfi stepping

forward as the little tech sidles out of nowhere, smiling. Just a

suggestion of a bow, and his left thumb falls off. It’s a conjuring

trick. The thumb hangs suspended. Mirrors? Wires? And Ralfi stops, his

back to us, dark crescents of sweat under the armpits of his pale summer

suit. He knows. He must have known. And then the joke-shop thumbtip, heavy

as lead, arcs out in a lightning, yo-yo trick, and the invisible thread

connecting it to the killer’s hand passes laterally through Ralfi’s

skull, just above his eyebrows, whips up, and descends, slicing the

pear-shaped torso diagonally from shoulder to rib cage. Cuts so fine that

no blood flows until synapses misfire and the first tremors surrender the

body to gravity.

Ralfi tumbled apart in a pink cloud of fluids,

the three mismatched sections rolling forward onto the tiled pavement. In

total silence.

I brought the gym bag up, and my hand convulsed.

The recoil nearly broke my wrist.

It must have been raining; ribbons of water cascaded

from a ruptured geodesic and spattered on the tile behind us. We crouched

in the narrow gap between a surgical boutique and an antique shop. She’d

just edged one mirrored eye around the corner to report a single Volks

module in front of the Drome, red lights flashing. They were sweeping

Ralfi up. Asking questions.

I was covered in scorched white fluff. The tennis

socks. The gym bag was a ragged plastic cuff around my wrist. "I

don’t see how the hell I missed him."

" ‘Cause he’s fast, so fast." She

hugged her knees and rocked back and forth on her bootheels. "His

nervous system’s jacked up. He’s factory custom." She grinned and

gave a little squeal of delight. "I’m gonna get that boy. Tonight.

He’s the best, number one, top dollar, state of the art."

"What you’re going to get, for this

boy’s two million, is my ass out of here. Your boyfriend back there was

mostly grown in a vat in Chiba City. He’s a Yakuza assassin."

"Chiba. Yeah. See, Molly’s been Chiba, too."

And she showed me her hands, fingers slightly spread. Her fingers were

slender, tapered, very white against the polished burgundy nails. Ten

blades snicked straight out from their recesses beneath her nails, each

one a narrow, double-edged scalpel in pale blue steel.

I’d never spent much time in Nighttown. Nobody

there had anything to pay me to remember, and most of them had a lot they

paid regularly to forget. Generations of sharpshooters had chipped away at

the neon until the maintenance crews gave up. Even at noon the arcs were

soot-black against faintest pearl.

Where do you go when the world’s wealthiest

criminal order is feeling for you with calm, distant fingers? Where do you

hide from the Yakuza, so powerful that it owns comsats and at least three

shuttles? The Yakuza is a true multinational, like ITT and Ono-Sendai.

Fifty years before I was born the Yakuza had already absorbed the Triads,

the Mafia, the Union Corse.

Molly had an answer: you hide in the Pit, in the

lowest circle, where any outside influence generates swift, concentric

ripples of raw menace. You hide in Nighttown. Better yet, you hide above

Nighttown, because the Pit’s inverted, and the bottom of its bowl

touches the sky, the sky that Nighttown never sees, sweating under its own

firmament of acrylic resin, up where the Lo Teks crouch in the dark like

gargoyles, black-market cigarettes dangling from their lips.

She had another answer, too.

"So you’re locked up good and tight,

Johnny-san? No way to get that program without the password?" She led

me into the shadows that waited beyond the bright tube platform. The

concrete walls were overlaid with graffiti, years of them twisting into a

single metascrawl of rage and frustration.

"The stored data are fed in through a

modified series of microsurgical contraautism prostheses." I reeled

off a numb version of my standard sales pitch. "Client’s code is

stored in a special chip; barring Squids, which we in the trade don’t

like to talk about, there’s no way to recover your phrase. Can’t drug

it out, cut it out, torture it. I don’t know it, never did."

"Squids? Crawly things with arms?" We

emerged into a deserted street market. Shadowy figures watched us from

across a makeshift square littered with fish heads and rotting fruit.

"Superconducting quantum interference

detectors. Used them in the war to find submarines, suss out enemy cyber

systems."

"Yeah? Navy stuff? From the war? Squid’ll

read that chip of yours?" She’d stopped walking, and I felt her

eyes on me behind those twin mirrors.

"Even the primitive models could measure a

magnetic field a billionth the strength of geomagnetic force; it’s like

pulling a whisper out of a cheering stadium."

"Cops can do that already, with parabolic

microphones and lasers."

"But your data’s still secure." Pride

in profession. "No government’ll let their cops have Squids, not

even the security heavies. Too much chance of interdepartmental funnies;

they’re too likely to watergate you."

"Navy stuff," she said, and her grin

gleamed in the shadows. "Navy stuff. I got a friend down here who was

in the navy, name’s Jones. I think you’d better meet him. He’s a

junkie, though. So we’ll have to take him something."

"A junkie?"

"A dolphin."

He was more than a dolphin, but from another

dolphin’s point of view he might have seemed like something less. I

watched him swirling sluggishly in his galvanized tank. Water slopped over

the side, wetting my shoes. He was surplus from the last war. A cyborg.

He rose out of the water, showing us the crusted

plates along his sides, a kind of visual pun, his grace nearly lost under

articulated armor, clumsy and prehistoric. Twin deformities on either side

of his skull had been engineered to house sensor units. Silver lesions

gleamed on exposed sections of his gray-white hide.

Molly whistled. Jones thrashed his tall, and more

water cascaded down the side of the tank.

"What is this place?" I peered at vague

shapes in the dark, rusting chain link and things under tarps. Above the

tank hung a clumsy wooden framework, crossed and recrossed by rows of

dusty Christmas lights.

"Funland. Zoo and carnival rides. ‘Talk

with the War Whale.’ All that. Some whale Jones is . . . ."

Jones reared again and fixed me with a sad and

ancient eye.

"How’s he talk?" Suddenly I was

anxious to go.

"That’s the catch. Say ‘hi,’

Jones."

And all the bulbs lit simultaneously. They were

flashing red, white, and blue.

"Good with symbols,

see, but the code’s restricted. In the navy they had him wired into an

audiovisual display." She drew the narrow package from a jacket

pocket. "Pure shit, Jones. Want it?" He froze in the water and

started to sink. I felt a strange panic, remembering that he wasn’t a

fish, that he could drown. "We want the key to Johnny’s hank,

Jones. We want it fast."

The lights flickered, died.

"Go for it, Jones!"

Blue bulbs, cruciform.

Darkness.

"Pure! It’s clean. Come on,

Jones."

White sodium glare washed

her features, stark monochrome, shadows elevating from her cheekbones.

The arms of the red

swastika were twisted in her silver glasses. "Give it to him," I

said. "We’ve got it."

Ralfi Face. No imagination.

Jones heaved half his armored bulk over the edge

of his tank, and I thought the metal would give way. Molly stabbed him

overhand with the Syrette, driving the needle between two plates.

Propellant hissed. Patterns of light exploded, spasming across the frame

and then fading to black.

We left him drifting, rolling languorously in the

dark water. Maybe he was dreaming of his war in the Pacific, of the cyber

mines he’d swept, nosing gently into their circuitry with the Squid

he’d used to pick Ralfi’s pathetic password from the chip buried in my

head.

"I can see them slipping up when he was

de-mobbed, letting him out of the navy with that gear intact, but how does

a cybernetic dolphin get wired to smack?"

"The war," she said. "They all

were. Navy did it. How else you get ‘em working for you? "

"I’m not sure this profiles as good

business," the pirate said, angling for better money. "Target

specs on a comsat that isn’t in the book –"

"Waste my time and you won’t profile at

all," said Molly, leaning across his scarred plastic desk to prod him

with her forefinger.

"So maybe you want to buy your microwaves

somewhere else?" He was a tough kid, behind his Mao-job. A

Nighttowner by birth, probably.

Her hand blurred down the front of his jacket,

completely severing a lapel without even rumpling the fabric.

"So we got a deal or not?"

"Deal," he said, staring at his ruined

lapel with what he must have hoped was only polite interest. "Deal."

While I checked the two recorders we’d bought,

she extracted the slip of paper I’d given her from the zippered wrist

pocket of her jacket. She unfolded it and read silently, moving her lips.

She shrugged. "This is it?"

"Shoot," I said, punching the RECORD

studs of the two decks simultaneously.

"Christian White," she recited,

"and his Aryan Reggae Band."

Faithful Ralfi, a fan to his dying day.

Transition to idiot/savant mode is always less

abrupt than I expect it to be. The pirate broadcaster’s front was a

failing travel agency in a pastel cube that boasted a desk, three chairs,

and a faded poster of a Swiss orbital spa. A pair of toy birds with

blown-glass bodies and tin legs were sipping monotonously from a Styrofoam

cup of water on a ledge beside Molly’s shoulder. As I phased into mode,

they accelerated gradually until their Day-Glo-feathered crowns became

solid arcs of color. The LEDs that told seconds on the plastic wall clock

had become meaningless pulsing grids, and Molly and the Mao-faced boy grew

hazy, their arms blurring occasionally in insect-quick ghosts of gesture.

And then it all faded to cool gray static and an endless tone poem in an

artificial language.

I sat and sang dead Ralfi’s stolen program for

three hours.

The mall runs forty kilometers from end to end, a

ragged overlap of Fuller domes roofing what was once a suburban artery. If

they turn off the arcs on a clear day, a gray approximation of sunlight

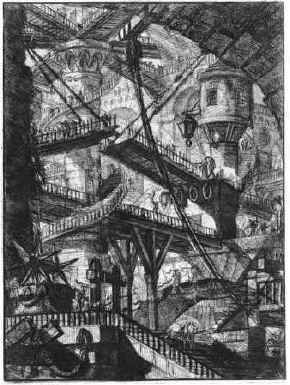

filters through layers of acrylic, a view like the prison sketches of Giovanni

Piranesi. The three southernmost kilometers roof Nighttown. Nighttown

pays no taxes, no utilities. The neon arcs are dead, and the geodesics

have been smoked black by decades of cooking fires. In the nearly total

darkness of a Nighttown noon, who notices a few dozen mad children lost in

the rafters?

We’d been climbing for two hours, up concrete

stairs and steel ladders with perforated rungs, past abandoned gantries

and dust-covered tools. We’d started in what looked like a disused

maintenance yard, stacked with triangular roofing segments. Everything

there had been covered with that same uniform layer of spraybomb graffiti:

gang names, initials, dates back to the turn of the century. The graffiti

followed us up, gradually thinning until a single name was repeated at

intervals. LO TEK. In dripping black capitals.

"Who’s Lo Tek?"

"Not us, boss." She climbed a shivering

aluminum ladder and vanished through a hole in a sheet of corrugated

plastic. " ‘Low technique, low technology.’ " The plastic

muffled her voice. I followed her up, nursing my aching wrist. "Lo

Teks, they’d think that shotgun trick of yours was effete."

An hour later I dragged myself up through another

hole, this one sawed crookedly in a sagging sheet of plywood, and met my

first Lo Tek.

" ‘S okay," Molly said, her hand

brushing my shoulder. "It’s just Dog. Hey, Dog."

In the narrow beam of her taped flash, he

regarded us with his one eye and slowly extruded a thick length of grayish

tongue, licking huge canines. I wondered how they wrote off tooth-bud

transplants from Dobermans as low technology. Immunosuppressives don’t

exactly grow on trees.

"Moll." Dental augmentation impeded his

speech. A string of saliva dangled from his twisted lower lip. "Heard

ya comin’. Long time." He might have been fifteen, but the fangs

and a bright mosaic of scars combined with the gaping socket to present a

mask of total bestiality. It had taken time and a certain kind of

creativity to assemble that face, and his posture told me he enjoyed

living behind it. He wore a pair of decaying jeans, black with grime and

shiny along the creases. His chest and feet were bare. He did something

with his mouth that approximated a grin. "Bein’ followed, you."

Far off, down in Nighttown, a water vendor cried

his trade.

"Strings jumping, Dog?" She swung her

flash to the side, and I saw thin cords tied to eyebolts, cords that ran

to the edge and vanished.

"Kill the fuckin’ light!"

She snapped it off.

"How come the one who’s followin’

you’s got no light?"

"Doesn’t need it. That one’s bad news,

Dog. Your sentries give him a tumble, they’ll come home in easy-to-carry

sections. "

"This a friend friend, Moll?" He

sounded uneasy. I heard his feet shift on the worn plywood.

"No. But he’s mine. And this one,"

slapping my shoulder, "he’s a friend. Got that?"

"Sure," he said, without much

enthusiasm, padding to the platform’s edge, where the eyebolts were. He

began to pluck out some kind of message on the taut cords.

Nighttown spread beneath us like a toy village

for rats; tiny windows showed candlelight, with only a few harsh, bright

squares lit by battery lanterns and carbide lamps. I imagined the old men

at their endless games of dominoes, under warm, fat drops of water that

fell from wet wash hung out on poles between the plywood shanties. Then I

tried to imagine him climbing patiently up through the darkness in his

zoris and ugly tourist shirt, bland and unhurried. How was he tracking us?

"Good, " said Molly. "He smells us."

"Smoke?" Dog dragged a crumpled pack

from his pocket and prized out a flattened cigarette. I squinted at the

trademark while he lit it for me with a kitchen match. Yiheyuan filters.

Beijing Cigarette Factory. I decided that the Lo Teks were black

marketeers. Dog and Molly went back to their argument, which seemed to

revolve around Molly’s desire to use some particular piece of Lo Tek

real estate.

"I’ve done you a lot of favors, man. I

want that floor. And I want the music."

"You’re not Lo Tek . . . ."

This must have been going on for the better part

of a twisted kilometer, Dog leading us along swaying catwalks and up rope

ladders. The Lo Teks leech their webs and huddling places to the city’s

fabric with thick gobs of epoxy and sleep above the abyss in mesh hammocks.

Their country is so attenuated that in places it consists of little more

than holds for hands and feet, sawed into geodesic struts.

The Killing Floor, she called it. Scrambling

after her, my new Eddie Bax shoes slipping on worn metal and damp plywood,

I wondered how it could be any more lethal than the rest of the territory.

At the same time I sensed that Dog’s protests were ritual and that she

already expected to get whatever it was she wanted.

Somewhere beneath us, Jones would be circling his

tank, feeling the first twinges of junk sickness. The police would be

boring the Drome regulars with questions about Ralfi. What did he do? Who

was he with before he stepped outside? And the Yakuza would be settling

its ghostly bulk over the city’s data banks, probing for faint images of

me reflected in numbered accounts, securities transactions, bills for

utilities. We’re an information economy. They teach you that in school.

What they don’t tell you is that it’s impossible to move, to live, to

operate at any level without leaving traces, bits, seemingly meaningless

fragments of personal information. Fragments that can be retrieved,

amplified . . .

But by now the pirate would have shuttled our

message into line for blackbox transmission to the Yakuza comsat. A simple

message: Call off the dogs or we wideband your program.

The program. I had no idea what it contained. I

still don’t. I only sing the song, with zero comprehension. It was

probably research data, the Yakuza being given to advanced forms of

industrial espionage. A genteel business, stealing from Ono-Sendai as a

matter of course and politely holding their data for ransom, threatening

to blunt the conglomerate’s research edge by making the product public.

But why couldn’t any number play? Wouldn’t

they be happier with something to sell back to Ono-Sendai, happier than

they’d be with one dead Johnny from Memory Lane?

Their program was on its way to an address in

Sydney, to a place that held letters for clients and didn’t ask

questions once you’d paid a small retainer. Fourth-class surface mail.

I’d erased most of the other copy and recorded our message in the

resulting gap, leaving just enough of the program to identify it as the

real thing.

My wrist hurt. I wanted to stop, to lie down, to

sleep. I knew that I’d lose my grip and fall soon, knew that the sharp

black shoes I’d bought for my evening as Eddie Bax would lose their

purchase and carry me down to Nighttown. But he rose in my mind like a

cheap religious hologram, glowing, the enlarged chip on his Hawaiian shirt

looming like a reconnaissance shot of some doomed urban nucleus.

So I followed Dog and Molly through Lo Tek heaven,

jury-rigged and jerry-built from scraps that even Nighttown didn’t want.

The Killing Floor was eight meters on a side. A

giant had threaded steel cable back and forth through a junkyard and drawn

it all taut. It creaked when it moved, and it moved constantly, swaying

and bucking as the gathering Lo Teks arranged themselves on the shelf of

plywood surrounding it. The wood was silver with age, polished with long

use and deeply etched with initials, threats, declarations of passion.

This was suspended from a separate set of cables, which lost themselves in

darkness beyond the raw white glare of the two ancient floods suspended

above the Floor.

A girl with teeth like Dog’s hit the Floor on

all fours. Her breasts were tattooed with indigo spirals. Then she was

across the Floor, laughing, grappling with a boy who was drinking dark

liquid from a liter flask.

Lo Tek fashion ran to scars and tattoos. And

teeth. The electricity they were tapping to light the Killing Floor seemed

to be an exception to their overall aesthetic, made in the name of . . .

ritual, sport, art? I didn’t know, but I could see that the Floor was

something special. It had the look of having been assembled over

generations.

I held the useless shotgun under my jacket. Its

hardness and heft were comforting, even though I had no more shells. And

it came to me that I had no idea at all of what was really happening, or

of what was supposed to happen. And that was the nature of my game,

because I’d spent most of my life as a blind receptacle to be filled

with other people’s knowledge and then drained, spouting synthetic

languages I’d never understand. A very technical boy. Sure.

And then I noticed just how quiet the Lo Teks had

become.

He was there, at the edge of the light, taking in

the Killing Floor and the gallery of silent Lo Teks with a tourist’s

calm. And as our eyes met for the first time with mutual recognition, a

memory clicked into place for me, of Paris, and the long Mercedes

electrics gliding through the rain to Notre Dame; mobile greenhouses,

Japanese faces behind the glass, and a hundred Nikons rising in blind

phototropism, flowers of steel and crystal. Behind his eyes, as they found

me, those same shutters whirring.

I looked for Molly Millions, but she was gone.

The Lo Teks parted to let him step up onto the

bench. He bowed, smiling, and stepped smoothly out of his sandals, leaving

them side by side, perfectly aligned, and then he stepped down onto the

Killing Floor. He came for me, across that shifting trampoline of scrap,

as easily as any tourist padding across synthetic pile in any featureless

hotel.

Molly hit the Floor, moving.

The Floor screamed.

It was miked and amplified, with pickups riding

the four fat coil springs at the corners and contact mikes taped at random

to rusting machine fragments. Somewhere the Lo Teks had an amp and a

synthesizer, and now I made out the shapes of speakers overhead, above the

cruel white floods.

A drumbeat began, electronic, like an amplified

heart, steady as a metronome.

She’d removed her leather jacket and boots; her

T-shirt was sleeveless, faint telltales of Chiba City circuitry traced

along her thin arms. Her leather jeans gleamed under the floods. She began

to dance.

She flexed her knees, white feet tensed on a

flattened gas tank, and the Killing Floor began to heave in response. The

sound it made was like a world ending, like the wires that hold heaven

snapping and coiling across the sky.

He rode with it, for a few heartbeats, and then

he moved, judging the movement of the Floor perfectly, like a man stepping

from one flat stone to another in an ornamental garden.

He pulled the tip from his thumb with the grace

of a man at ease with social gesture and flung it at her. Under the floods,

the filament was a refracting thread of rainbow. She threw herself flat

and rolled, jackknifing up as the molecule whipped past, steel claws

snapping into the light in what must have been an automatic rictus of

defence.

The drum pulse quickened, and she bounced with it,

her dark hair wild around the blank silver lenses, her mouth thin, lips

taut with concentration. The Killing Floor boomed and roared, and the Lo

Teks were screaming their excitement.

He retracted the filament to a whirling

meter-wide circle of ghostly polychrome and spun it in front of him,

thumbless hand held level with his sternum. A shield.

And Molly seemed to let something go, something

inside, and that was the real start of her mad-dog dance. She jumped,

twisting, lunging sideways, landing with both feet on an alloy engine

block wired directly to one of the coil springs. I cupped my hands over my

ears and knelt in a vertigo of sound, thinking Floor and benches were on

their way down, down to Nighttown, and I saw us tearing through the

shanties, the wet wash, exploding on the tiles like rotten fruit. But the

cables held, and the Killing Floor rose and fell like a crazy metal sea.

And Molly danced on it.

And at the end, just before he made his final

cast with the filament, I saw something in his face, an expression that

didn’t seem to belong there. It wasn’t fear and it wasn’t anger. I

think it was disbelief, stunned incomprehension mingled with pure

aesthetic revulsion at what he was seeing, hearing – at what was

happening to him. He retracted the whirling filament, the ghost disk

shrinking to the size of a dinner plate as he whipped his arm above his

head and brought it down, the thumbtip curving out for Molly like a live

thing.

The Floor carried her down, the molecule passing

just above her head; the Floor whiplashed, lifting him into the path of

the taut molecule. It should have passed harmlessly over his head and been

withdrawn into its diamond-hard socket. It took his hand off just behind

the wrist. There was a gap in the Floor in front of him, and he went

through it like a diver, with a strange deliberate grace, a defeated

kamikaze on his way down to Nighttown. Partly, I think, he took the dive

to buy himself a few seconds of the dignity of silence. She’d killed him

with culture shock.

The Lo Teks roared, but someone shut the

amplifier off, and Molly rode the Killing Floor into silence, hanging on

now, her face white and blank, until the pitching slowed and there was

only a faint pinging of tortured metal and the grating of rust on rust.

We searched the Floor for the severed hand, but

we never found it. All we found was a graceful curve in one piece of

rusted steel, where the molecule went through. Its edge was bright as new

chrome.

We never learned whether the Yakuza had accepted our

terms, or even whether they got our message. As far as I know, their

program is still waiting for Eddie Bax on a shelf in the back room of a

gift shop on the third level of Sydney Central-5. Probably they sold the

original back to Ono-Sendai months ago. But maybe they did get the

pirate’s broadcast, because nobody’s come looking for me yet, and

it’s been nearly a year. If they do come, they’ll have a long climb up

through the dark, past Dog’s sentries, and I don’t look much like

Eddie Bax these days. I let Molly take care of that, with a local

anesthetic. And my new teeth have almost grown in.

I decided to stay up here. When I looked out

across the Killing Floor, before he came, I saw how hollow I was. And I

knew I was sick of being a bucket. So now I climb down and visit Jones,

almost every night. We’re partners now, Jones and I, and Molly Millions,

too. Molly handles our business in the Drome. Jones is still in Funland,

but he has a bigger tank, with fresh seawater trucked in once a week. And

he has his junk, when he needs it. He still talks to the kids with his

frame of lights, but be talks to me on a new display unit in a shed that I

rent there, a better unit than the one he used in the navy.

And we’re all making good money, better money

than I made before, because Jones’s Squid can read the traces of

anything that anyone ever stored in me, and he gives it to me on the

display unit in languages I can understand. So we’re learning a lot

about all my former clients. And one day I’ll have a surgeon dig all the

silicon out of my amygdalae, and I’ll live with my own memories and

nobody else’s, the way other people do. But not for a while.

In the meantime it’s really okay up here, way

up in the dark, smoking a Chinese filtertip and listening to the

condensation that drips from the geodesics. Real quiet up here – unless

a pair of Lo Teks decide to dance on the Killing Floor.

It’s educational, too. With Jones to help me

figure things out, I’m getting to be the most technical boy in town. |

|